This post explains the cybernetic concepts behind Panic, an interactive artwork at the Australian Cybernetic exhibition in Nov/Dev 2022. That exhibition is now over—thanks very much to all who came along. If you missed out on seeing it, there are exciting plans in the works to re-install Panic somewhere more permanent. Nothing’s confirmed just yet, but stay tuned ☺

Time and society provide us with images of the world. Each generation takes the image and changes it, a bit, or a lot. Our images undergo greater changes than we do ourselves.

Jaisa Reichardt, Our Dreams Change, We Don’t (2019)

Panic is a new interactive artwork created by my colleague Adrian Schmidt and I which premiered at the Australian Cybernetic: a point through time exhibition at the ANU School of Cybernetics in December 2022. This new exhibition revisits Jaisa Reichardt’s influential 1968 Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition, and introduces new reflections on contemporary approaches to cybernetics underway at the ANU.

How does Panic work?#

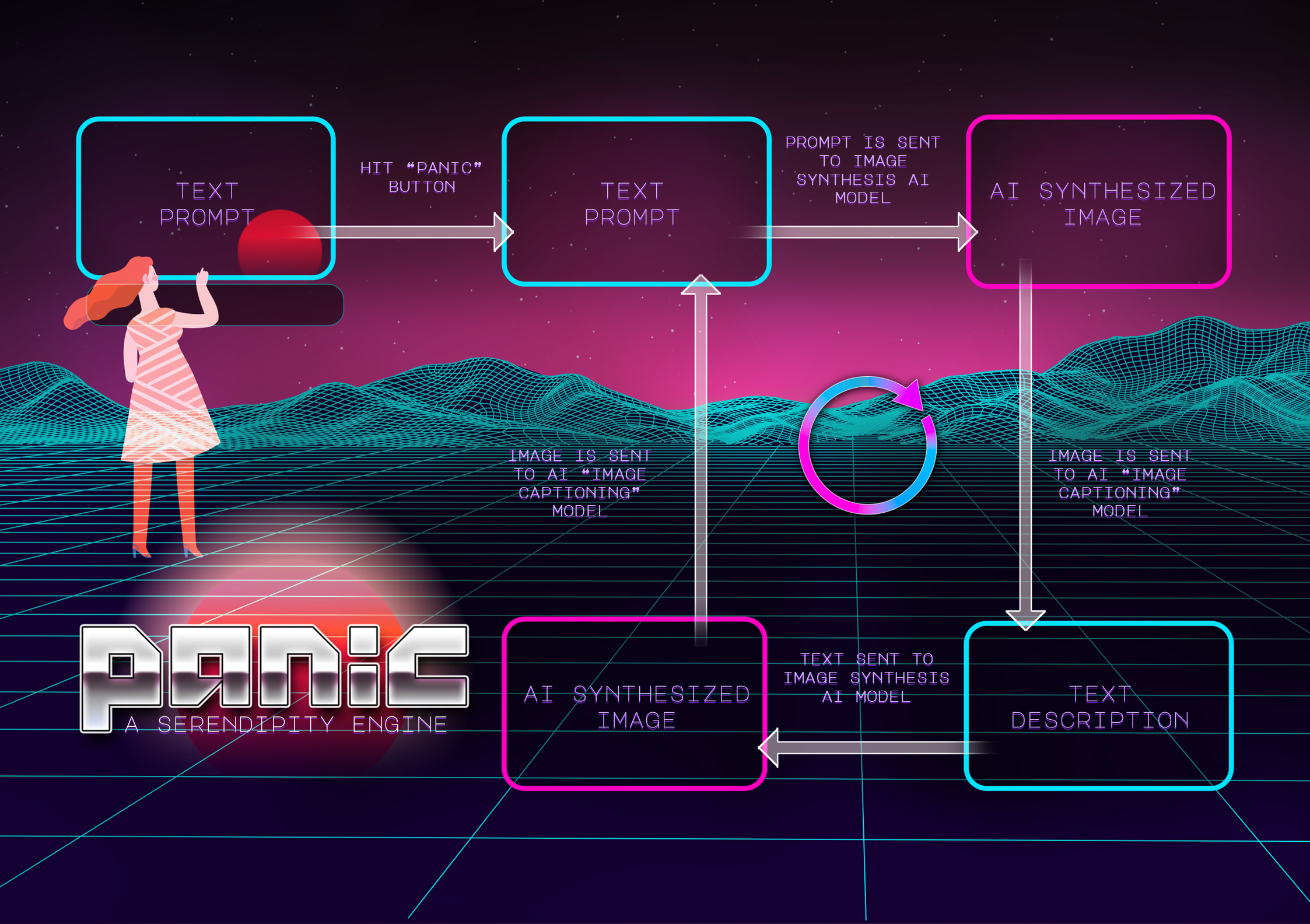

Panic works by taking the viewer’s1 text input (typed on a conventional computer keyboard) and running it through three AI models, one after the other.

-

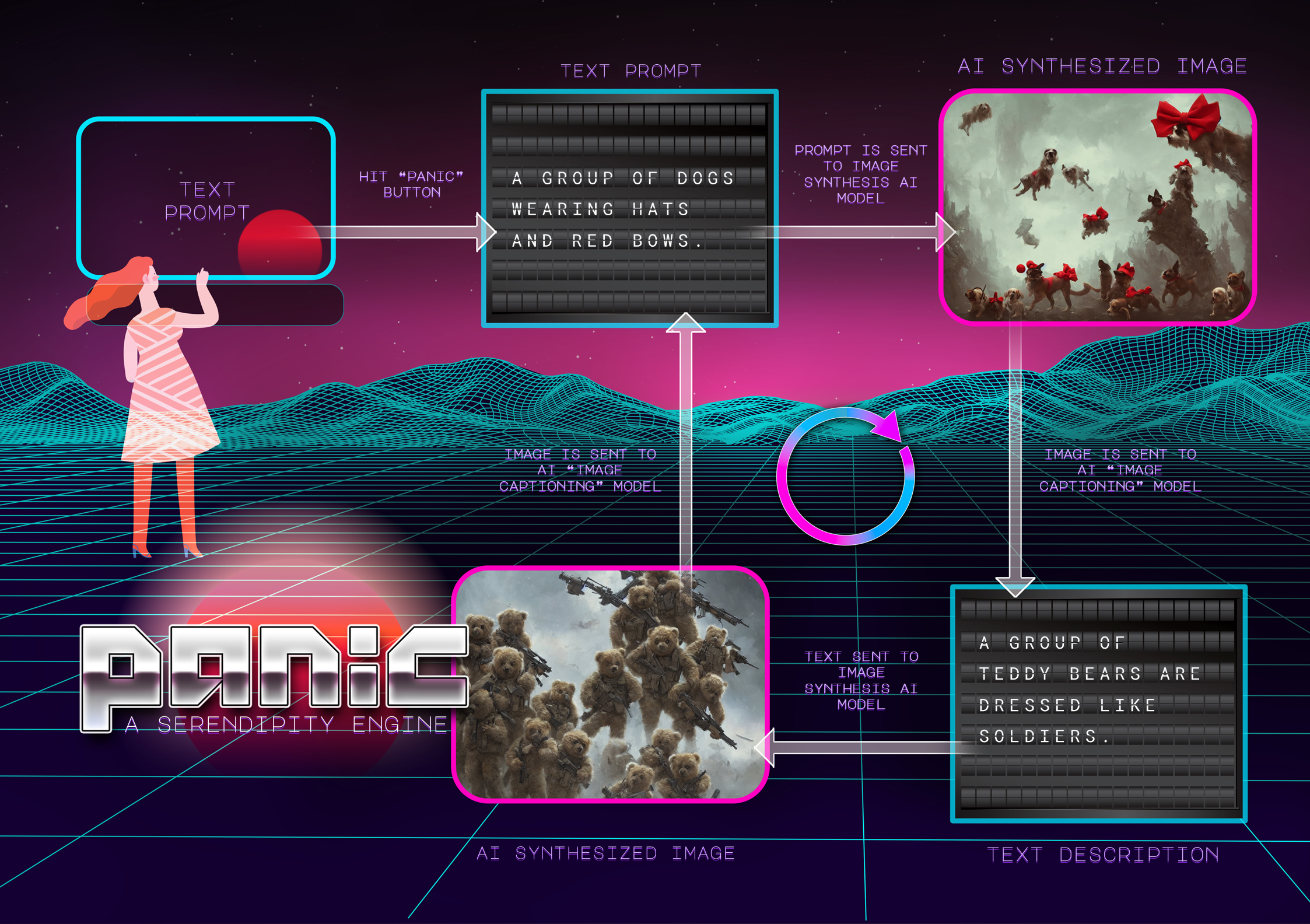

Prompt Parrot is a text-to-text model. It takes a short sentence as input and adds extra text descriptions (e.g. adjectives like “beautiful” or “high quality”) to the end of the input text as output.

-

Stable Diffusion is a text-to-image model. It takes a the Prompt Parrot-generated text as input and generates an image “matching” that description as output.

-

CLIP Prefix Caption is an image-to-text model which takes the Stable Diffusion-generated image as input and produces a text “caption” which describes the image as output. This text caption output can then be fed back into the Prompt Parrot as input, and this process repeats indefinitely

Here’s a diagram of the main concept:

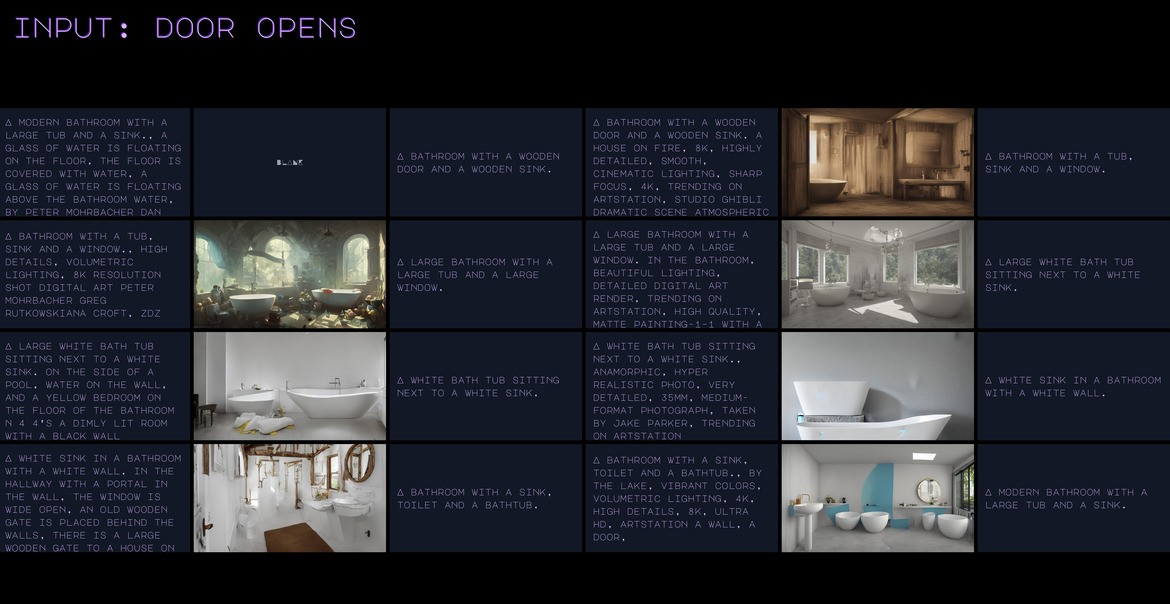

and a similar one, but with example inputs & outputs to make things a bit more concrete:

And here’s a video of Panic in action:

If you’re interested in more detail about the tech stack see the FAQ at the end of this post. But what’s most interesting about Panic isn’t necessarily what it is, but what it shows us about AI models, humans, and feedback loops, and steering complex systems of people and technology.

Even AI images and text are made by humans#

You’ve probably heard about recent advances in AI models which can draw pictures and write text in response to input “prompts”. For example, you can tell the computer to draw “a picture of an astronaut riding a horse”2 and you’ll get something which looks like a picture of an astronaut riding a horse.

This image/text synthesis thing isn’t new—Michael Noll has the receipts from more than 50 years ago:

Digital computers are now being used to produce musical sounds and to create artistic visual images. The artist or computer interacts directly with the computer through a console.

A Michael Noll, The Digital Computer as a Creative Medium (1967)

However it is fair to say that we’re now at a stage where these AI-generated text and images can reliably pass as “human-made”. Some of the examples examples online are pretty impressive. Even for those (like me) who play close attention to this stuff the gains in the last couple of years have been amazing.

If you play with Panic for a while you’ll probably notice that the images produced by the Stable Diffusion AI model (which show up on the TV screens) are at times confronting, beautiful, surprising, weird, or a bit “off”—sometimes all of the above. They’re certainly (in general) interesting to humans; they’re legible to us within the broad category of “aesthetic images”.

And we shouldn’t be surprised at that, because the billions of images in the Stable Diffusion training set were created by humans. As my colleague Ellen Broad says this stuff was “made by humans”.

That’s true of the text models as well—both the the prompt parrot and image captioning model. These models are created by feeding in huge amounts of human-created data, from which the model learns to generate (statistically) similar outputs. The Prompt Parrot model is a particularly interesting case, and then used that information to create a new AI model which will “write” text for other AI models.

The AI-generated text outputs therefore include spelling mistakes and other hallmarks of the human-written text, because that’s what they’re made of. And if you watch Panic as it progresses through various AI-generated text and image outputs, you’ll no doubt see these traces of humanity popping up from time to time.

Things to think about (or discussion questions if you’re visiting Panic with a friend):

-

which of the AI-generated text/images seem most like they could have been generated by a human? which ones seem least like they could have been generated by a human? why?

-

do you notice the AI-ness of the text/images more or less as time (and the sequence of text/images) goes on?

Serendipity through iteration#

You don’t need to come see Panic to use an AI text/image generator, though—you can do that for free on the internet. But it’s a mistake to think about these AI art generators in terms of one-shot “I give the AI model an input, and it gives me back an output” exchanges.

Instead, panic encourages the viewer to think about how they’ll connect and become enmeshed in the flows of information already present in our world. In particular, what happens when the output of one model is fed back in as the input to the next one, and so on ad infinitum? This behaviour—where the output of a system is “fed back” in as a new input—is called a feedback loop.

And that’s how Panic works. Until you re-start the cycle by typing in a new prompt (and pressing the panic button), it’ll run forever. Even if you give it the same input prompt twice in a row you’ll get different image outputs—in fact the image generator works by effectively selecting one image from billions of different potential output images for a given input text.

The artistic potential of The potential of these closed “feedback loops” in art has a long history, most notably in the work of video art pioneer Nam June Paik (who was featured in the Cybernetic Serendipity ‘68 exhibition).

For these early media artists, the feedback loops, live circuits, and video flows, coupled with the electronic image’s immediate and physiological stimulations, when used in distinction to commercial models, posited potent possibilities for cybernetic consciousness, ecological human-machine systems, and an end to top-down power relations.

Carolyn Kane, The Cybernetic Pioneer of Video Art: Nam June Paik (2009)

Artist Mario Klingemann (@quasimondo), whose work Appropriate Response (2020) is an obvious inspiration for Panic (both in its use of AI-generated text but also in the split-flap displays), says something similar:

Whilst it might appear that Appropriate Response is very different, or does not fit into my previous work—which people might think is only about images or moving pictures—for me it very much fits in because my work is actually about systems and about information and the way we perceive it.

Mario Klingemann, Appropriate Response (2020)

If you sit with Panic for a while (and that’s why there are chairs around the room) you might be surprised by where the output “goes”. For a while the AI images will be bouncing around green fields full of sheep, then the image captioning model might “notice” a plane in the sky, and within just a few iterations of the feedback loop you’re looking at robots battling each other in a neon futuristic city3.

It can be exiting to watch, and it’s really hard to predict what the longer-term trajectory of any given input will be. Panic is a chance to explore the cumulative effect of many different AI image iterations, which can lead to surprising—even serendipitous—places.

More than just generating interesting (and sometimes cooked) text/image outputs, the purpose of Panic is to explore how different ways of connecting AI models—different “network topologies” to use fancy mathematical language—can give rise to different outputs. Where are the “attractors” in the phase space of all possible inputs, and where are the phase transitions? Does it even matter what the initial prompt is, will Panic eventually converge to pictures of cats (the “unofficial mascot of the internet”)?

Things to think about (or discussion questions if you’re visiting Panic with a friend):

-

here’s an interesting game: for a given input, try and guess what the images will will look like after 10 iterations… or 100 iterations

-

the same game in reverse: describe an image (e.g. thunder in the night sky) and try and find an initial text prompt which will generate a picture of that thing after 10 iterations… or 100 iterations

-

how much do you think the initial prompt matters? or is it only the AI models themselves (maybe some more than others?) which make a difference after the first few iterations?

-

do you think it’ll ever get “stuck” generating one type of image forever, or will it always eventually “bounce out” to draw something else?

Camel erasure and emergent bias#

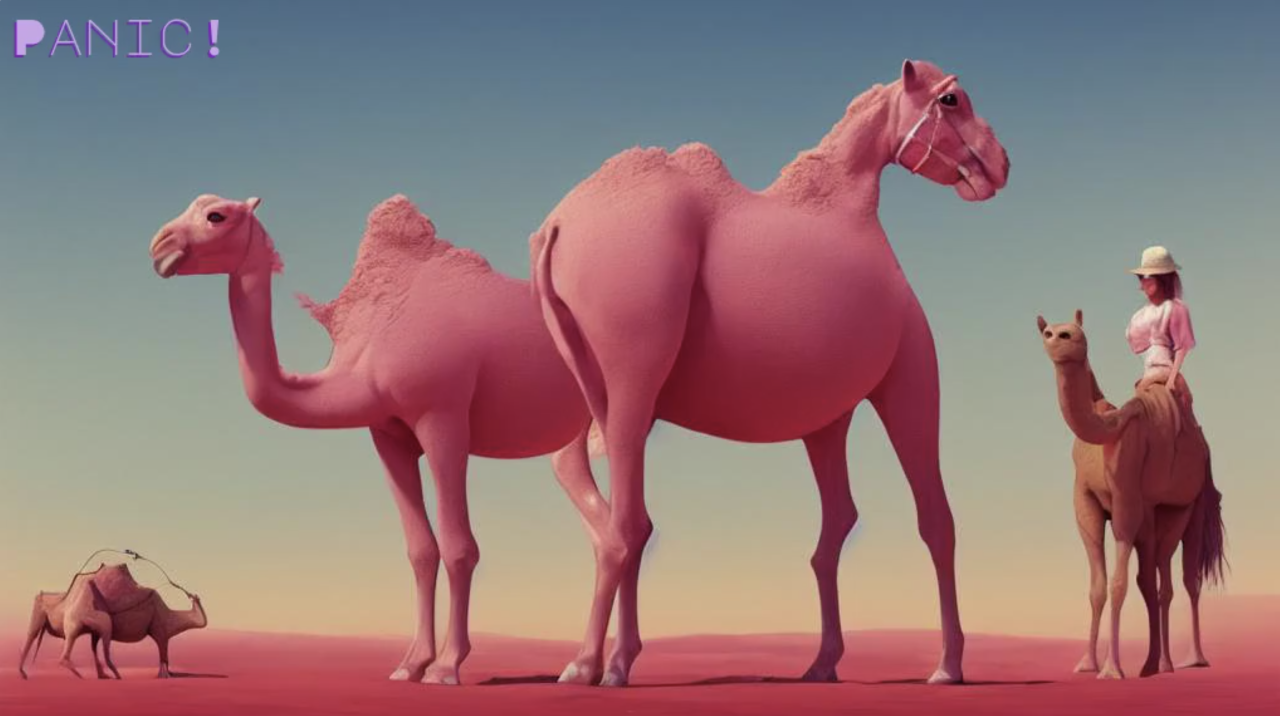

Our School Director loves to put inputs about camels into Panic!, but noticed that the camels didn’t stick around in the model outputs as they were fed through the model loop:

So, I’ve put in four prompts with camels as the primary noun. It always produces a camel in round one, but reading that image never produces a camel. It ranges from sheep, horses and cattle to ALL THE GIRAFFES :-)

After some followup testing we confirmed that Panic! (at least with the current network of AI models) does indeed suffer from a “camel erasure” problem. Specifically, the captioning model doesn’t seem to recognise pictures of camels. The stable diffusion image-to-text model in round one (from the initial prompt) can draw camels just fine, but then that output goes into the first captioning model—and from then on it’s giraffes all the way down (until you hit the turtles). There’s a lesson here about how if parts of your system are missing certain voices, that can mean those voices get erased from the behaviour of the entire system. Bias isn’t just a property of individual models, it’s an emergent property of complex systems.

From a “what does cybernetics say about this” point of view there’s a bigger point here about resonance. The awkward screech when someone turns a PA microphone up too loud requires a feedback loop, but the thing we notice (the screech) is the resonant frequency—which is an emergent property of the speakers, amplifiers, mic, room, the bodies in it, etc. Panic is one way of ringing out a particular configuration of AI models to see where the resonances are.

The camel erasure story has a happy ending, though: after going through all the outputs from the Australian Cybernetic exhibition we did find one (and only one) instance of the captioning model spitting out the word camel. Starting from the initial prompt “android sheep”, 46 outputs later we got the caption “A pink horse and a pink camel in a desert” and the following image:

How does one steer a system like Panic?#

This “serendipity through iteration” behaviour hints at deeper challenges in a world of networked AI models. Panic is “just” an artwork, so if you can’t steer it to produce (or avoid) a certain output then it’s no big deal. But if the AI models are dealing with our private personal data or enforcing our quarantine policies then it’s more crucial that we understand what the range of the AI model’s future inputs and outputs might be.

Panic doesn’t magically solve the outstanding challenges in steering complex AI systems. But steering is something that cybernetics has a lot to say about, and there’s one more key cybernetic concept which Panic can illustrate: second-order cybernetics.

Apart from Panic’s eight main displays (showing the four most recent images and four most recent text outputs respectively) there’s one more large display screen in the exhibit. This screen shows the (current) initial text input plus the last thirty inputs & outputs from the AI models. With this “zoomed out” picture the viewer can really see the way the initial prompt evolves as it moves through the network of models. Humans are pattern recognition machines, and the viewer’s work-in-progress undertsanding of how the AI models responded to the current prompt will inevitably shape their next prompt. For example, if Panic gets stuck in a cycle of cats, the viewer’s next prompt may be about a dog, or it may be an abstract concept completely unrelated to people or animals. And the way that Panic responds to that prompt will shape the next one, and so on.

The output-of-one-as-input-to-the-next aspect of Panic’s AI “model networks” makes it interesting to observe over time. But there’s another level of feedback going on—between the viewer and the system itself, unfolding across successive input prompts. The viewer’s behaviour is shaped by the system, and vice versa—that’s second-order cybernetics. Put another way, there’s no passive “view from outside” of the system, the viewer is always a part of the system they’re viewing.

Crucially, the text/image outputs of the models inputs and outputs are displayed to the viewer—they don’t just put in the initial prompt and then have the final output emailed to them later (in fact, there is no final output from a Panic, because the text and images will keep looping forever). And each of these intermediate outputs is also legible (because humans are really good at making sense of text and images).

This isn’t the case for large AI models in general—which have lots of intermediate steps in their processing, but each intermediate steps can only be represented as vast arrays of data—millions and millions of numbers—which computers are good at processing, but humans really aren’t. So the fact that there are at least some intermediate steps which are visible and comprehensible to the viewer is a crucial part of making use of that second-order feedback loop.

The viewer feels like they have some control, but only in a limited fashion. Again, Michael Noll:

Specified amounts of interaction and modification might be introduced by the individual, but the overall course of the interactive experience would still follow the artist’s model… Only those aspects deliberately specified by the artist might be left to chance or to the whims of the participant.

A Michael Noll, The Digital Computer as a Creative Medium (1967)

Panic allows the viewer—and anyone else watching—to observe, re-prompt, re-observe, to build and test theories about how this all works, and hopefully to still be surprised by the serendipity of the iterative outputs of the system. The viewer will still leave with many questions—probably more than they walked in with—but also a new appreciation for AI text/image synthesis models: made by humans, serendipitous through iteration, and (maybe) steerable via second-order cybernetics.

Anyway, we hope you’ll come visit us at the Australian Cybernetic: a point through time exhibition and experience Panic for yourself.

Things to think about (or discussion questions if you’re visiting Panic with a friend):

-

to what degree is your next prompt shaped by the way you saw your previous one as it iterated through the system?

-

is there any other information/feedback would you like to know about each text/image output as Panic runs?

-

does it change your view of AI models as input-output “black boxes”? if so, how?

The Australian Cybernetic exhibition is now over, but if you want to turn on, tune in and drop out to a 90min YouTube video of every single AI-generated image from the whole two weeks of the exhibition, you’re in luck.

FAQ#

If you’ve still got questions about Panic, this FAQ might answer them.

Why is it called Panic?#

It’s an acronym: Playground AI Network for Interactive Creativity. Well, it’s probably more of a backronym.

There’s also another layer to the name evoking the general sense of unease (perhaps rising to mild panic) that some of us feel when we think about the widespread use of AI models in the world today.

Finally, there’s the fact that it allowed us to have a big, red, light-up “Panic button”.

You may wonder what the “playground” part in the acronym is talking about. Panic is actually designed to work with any creative AI model, and to allow the artist to set up different model “network topologies” to see how different text/audio/image inputs are transformed as they are passed through different Creative AI networks. This allows the artist to observe emergent behaviours, recurring patterns, degenerate/edge cases, and what it all says about the nature of Creative AI model platforms in their current form.

However, for the Australian Cybernetic: a point through time exhibition we have chosen a specific AI model “network” of the three models described above.

Inputs and Sensors: what information/data does this capture?#

The installation contains a computer (QWERTY) keyboard, which participants can use to provide text input to the AI models.

What information/data is saved to disk (either here or in the cloud)?#

The text and images you see on the screens are generated by AI models hosted at the Replicate cloud AI platform.

The Replicate cloud AI platform does store information about the text/image inputs and outputs of these models, and also metadata about when the image was generated (including the IP address of the request, from which it may be possible to deduce that Panic is based at the ANU). This data will be stored by Replicate and associated with the ANU School of Cybernetics’ account, and will not be traced back to any individual user. For more information, see the Replicate privacy policy.

Is there anything I should be concerned about?#

The Stable Diffusion AI model includes a content safety filter (similar to “Safe Search” setting for Google search results) which is designed to filter out any inappropriate images (e.g. nudity, gore). However, the accuracy of this content safety filter cannot be guaranteed. We recommend that children have adult supervision when interacting with Panic, and request that users be mindful of others when putting in their text prompts. In the unlikely event that inappropriate content is displayed, please alert a staff member.

What’s the tech stack?#

In terms of the hardware, the split-flap displays are made by Vestaboard, and the flat-panel TVs are from TCL, and each one is using the Amazon Silk web browser app (running on the Smart TV) to show a regular website. The cockpit (where users can provide their input) is a custom laser-cut enclosure of our own design, with screen/keyboard/panic button all hooked to a Raspberry Pi.

The main software component is a custom web app which provides the main “prompt input” interface, the displays the text and images across the various screens, and also makes the requests to the various Replicate cloud AI models. The web app is written in Elixir/Phoenix and uses LiveView to synchronise the various inputs & outputs across various devices.

What’s the connection to the ANU School of Cybernetics?#

At the School of Cybernetics we love thinking about the way that feedback loops (and the connections between components in general) shape the behaviour of the systems in which we live, work and create. That interest sits behind the design of Panic as a tool for making (and breaking!) networks of hosted Creative AI models.

While Panic is an experimental tool for creative “play”, the accessibility of these AI model platforms (cost, time, technical knowledge) means that their inputs & outputs are being increasingly taken up in the flows of people & culture which traverse our world—participating in both human and non-human feedback loops. Panic is a playground for leaning in to that connectivity to better understand where that road leads.

How can I find out more information?#

Send us an email at ben.swift@anu.edu.au or adrian.schmidt@anu.edu.au with “Panic” in the subject line and we’d love to chat.