Our world is rapidly approaching an ecological tipping point as climate change takes hold and biodiversity declines. Beyond reducing emissions and developing carbon capture technologies, experts have issued urgent calls for preserving nature. Artificial-intelligence-enabled cyber-physical systems (AI-CPS) have been proposed as a crucial tool to help us scale our conservation efforts. Around the world, these systems are being deployed to monitor wildlife, fight poaching, model ecosystems and simulate ecological interventions (Kwok, 2019).

However, a little known fact is that Indigenous people manage or have tenure rights on around a quarter of Earth’s land surface, and some experts estimate that this contains much of the world’s remaining biodiversity (Garnett et al., 2018). Therefore, AI-enabled conservation technologies will be and are already being used by Indigenous people to care for Country. This raises important questions about the design of culturally responsible technology that empowers them to make more informed decisions while respecting indigenous values.

These were the central questions of my Master of Applied Cybernetics capstone, where I worked with the CSIRO in the Healthy Country AI project. The Healthy Country AI is an artificial-intelligence-enabled cyber-physical system that integrates humans, computers and the environment in a first of its kind effort to support caring for Country. In particular, the system was developed in collaboration with Bininj Traditional Owners and Indigenous rangers to support management of invasive weeds that are decimating local biodiversity and cultural practices in Kakadu.

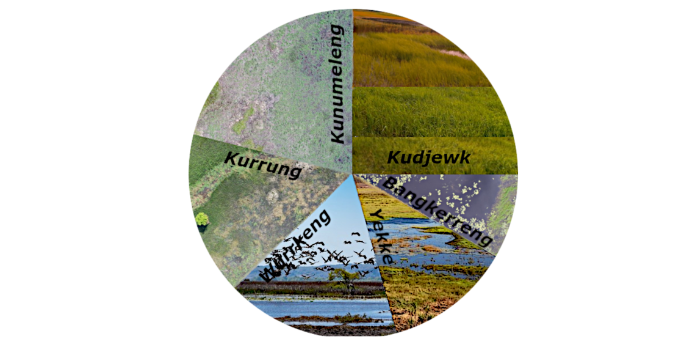

The Healthy Country AI CPS uses drones to survey the land, machine learning algorithms to classify aerial images and cloud technology to visualise infestation maps. Algorithms and data management were trained integrating traditional knowledge. For example, the Bininj six-season calendar was used to classify drone footage according to a traditional six-season calendar and a novel data privacy framework was developed to reflect how the community manages access to knowledge.

Before Healthy Country AI, Indigenous rangers made management actions with little information about the extent and spatial distribution of the weed infestation. Having a map enabled them to make more informed decisions, which eventually led to a rebound in biodiversity. However, the scale of the infestation is such that even with a map, it is difficult to estimate the impact of management actions and plan optimal allocation of very limited resources.

So the task presented to me was the following: how can we turn these large volume of data into action more effectively, while integrating novel algorithms with culturally responsible practices? This was an ideal application of the learnings for the Masters, as it involves a cyber-physical system and a complex problem that touches on people, technology and the environment.

I engaged with stakeholders and experts that shared with me decades of expertise and specific knowledge about the system and its application on Country. Through an iterative process, I developed an algorithm to simulate management actions and subsequent weed spread. With this, I created a tool called Strategy Planner that lets rangers compare the outcomes of different strategies in an interactive dashboard. They can select different alternatives, and see the effect that each would have on Country. The tool seeks to engage and serve a scenario planning tool, rather than a prescriptive one. Instead of replacing their judgment, the tool was developed to support their own decision-making.

I learned several lessons along the way, and I would like to share some of them for fellow cybernetic practitioners, and anyone interested in developing technology at the intersection of culture, people and the planet.

We need new ontologies for AI design

Technology is always a reflection of a particular culture and place. It is never neutral. In a 2017 talk, Genevieve Bell proposed an exercise where we append a label to AI in order to highlight how that technology reflects a particular world view. For example, we can ask what is an Australian AI and how it differs to plain AI. By doing so, we realise that such a “plain AI” is not really plain, but Silicon Valley AI. As such, it is very unlikely to have kangaroos in its ontology. An autonomous car equipped with this technology would face disastrous consequences when faced with a jumping object in the middle of a red dirt road.

Similarly, if we ask what is Bininj AI and how it differs from “plain AI” we can come to illuminating realisations. For example, drone images used to train the machine learning models in the Healthy Country AI are stored and classified by date. Initially, one would not think twice about the date system used. However, our default system, the Gregorian calendar, is only the default for a particular culture. In contrast, the Bininj use a unique six-season calendar defined by subtle changes in skies, rainfall, plants and animals. Therefore, if our AI fails to include this, our system will not only perform worse at classifying images, but will also be less accessible and inclusive to local people.

Design systems that support rather than replace human judgement

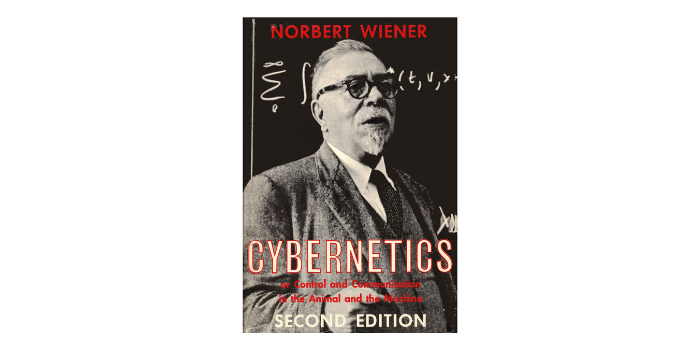

State-of-the-art AI research seems to be focused on automating and replacing human skills: language generation, medical diagnosis, game playing. To understand why, we have to look back to one of the foundational moments of AI, the Dartmouth conference of ‘56. Minsky and company set out the explicit goal of replicating human intelligence with computers. Since then, metrics of AI success have been defined in terms of beating humans at certain tasks. But another way of thinking about technology, intentionally left out from that conference, was Norbert Wiener’s cybernetics. Instead of thinking of how computers could replicate human skills, Wiener’s cybernetics focused on developing a science of communication between humans and machines. He conceived them not as replacements for one another, but as parts of a complex system of feedbacks and interactions.

I used this cybernetic premise to design the Healthy Country AI Strategy Planner. Algorithms simulate millions of alternatives in seconds, and humans bring critical judgement and culturally situated decision-making. But how does this mutually strengthening interaction happen? Interfaces as points of interaction between complex systems play a crucial role. Therefore, I focused a large portion of my time designing an interface where both algorithms and humans work together, each bringing a unique strength to face a complex problem such as invasive species management.

Include, co-design and empower local communities

Over many years, the field of conservation has learned that effective and sustained action hinges on local community collaboration. This remains true in an era of increasing use of artificial intelligence for ecological monitoring. Such technology has the capacity to transform people’s relations to country as well as to enable the scaling of actions that allow them to care for it. Collaborative design and community-led design can empower local and Indigenous communities to guide technology development along a path respects and aligns with their values.

Final thoughts

This has been one of the most enriching experiences of my life, and it has already led me to work with CSIRO in new projects. For example, I am now working on similar systems across Australia. A couple of weeks ago, I travelled to Cape York as part of a project that is tagging feral animals with satellite trackers to help traditional owners better manage their land. When I was in Mexico two years ago, learning that I was selected to be part of the 3Ai Masters, I never imagined that it would lead me to be chasing cows in the Australian outback and singing around a fire with Traditional Owners and CSIRO scientists. But as unlikely as it sounds, this experience reminded me once again that technology is always about people, and that was the reason I came here in the first place.

Thanks and acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the Ngunnawal people, traditional custodians of the land in which I was based during my capstone, as well as the Bininj people, on whose lands the Healthy Country AI project is being developed. I would also like to thank Cathy Robinson, Justin Perry, Jennifer McDonald, Vanessa Adams, Samatha Setterfield, Michael Douglas and Johan Michalove who provided invaluable guidance along the way. I would also like to thank the Harrigan brothers, Vince, Pando, and Cliff who received me in their Country up in Normanby for an unforgettable experience.

References

Garnett, S. T., Burgess, N. D., Fa, J. E., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Molnár, Z., Robinson, C. J., Watson, J. E. M., Zander, K. K., Austin, B., Brondizio, E. S., Collier, N. F., Duncan, T., Ellis, E., Geyle, H., Jackson, M. V., Jonas, H., Malmer, P., McGowan, B., Sivongxay, A., & Leiper, I. (2018). A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nature Sustainability, 1(7), 369–374. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0100-6

Kwok, R. (2019). AI empowers conservation biology. Nature, 567(7746), 133–134. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-00746-1