This Photo Essay was exhibited at the UN Water Conference official side event “The United Nations of Rivers, Deltas and Estuaries – Day 6 Engaging water: Artistic Workshops”, New York Water Week, 22 March 2023.

Interview with Prof. Katherine Daniell following the UN Riverwalk process, 9 Mar 2023.

What does this place mean to you, and can you reflect on your relationship to it?#

This is one of those spots that I feel a strong connection to. It’s one of my favourite places in the world to just sit and be. Every moment I spend here, the place is different. The water moves and transports things. The light, vegetation, and feel of the air changes. And I change and adapt in relation to being a part of it. Today the place is really green—unusually green, likely due to three years of La Niña, and the water is particularly noisy and boisterous. Unless we listen with a microphone under the water, it even drowns out the sounds of the crickets!

I remember a couple of years ago, being able to come here was really important because we’d just had our lockdowns, a pandemic, and the rest of the world was still locked down. Sydney was still locked down, and this was about as far away as we could get from our homes in Canberra and the online worlds. To be able to get outside and to reconnect with something that seemed wholesome was deeply important.

The other interesting thing about being here today is the change I can see. It’s now a few years since I was last here, and in the summer just prior to that moment, we’d had our huge bushfires across the country. This area hadn’t escaped those fires, so all of the bottoms of the trees were black. There was a carpet of new green bracken, but it was almost as if the tops of the trees hadn’t noticed the fire had been there. It was really kind of strange, an exciting but also slightly scary or eerie kind of time when it was possible to both be in place and also see these echoes of the past.

One of the other things that I reflect on when I come down here is wondering who has connected to this place before me, and still is today. From what I’ve been able to read and talk to local people about, this particular place in the valley is a women’s place, an Aboriginal women’s place. Moreover it’s a place where many different groups have gathered over millennia, back to at least the last ice age. This river was named Gibraltar Creek during colonial settlement of the area. In the creek upstream there are the falls, and that is apparently a men’s place, an important and sacred place of ceremony and initiation. So it is an important area for the First Nations peoples of this region—the Ngunnawal traditional custodians and adjoining groups. If you then go a little bit further along this tributary, you get to the Birrigai Rock Shelter, and further on you get to the place where the Bogong moths come—a place where many people came and connected, feasted, and celebrated.

This place has changed quite a bit since colonial settlement. The valley here is what’s now called Woods Reserve, named after a couple of the colonial settlers of the time, Edward and Julia Woods. But this has been a place where lots of families could come and connect, and it’s been that way for a couple of centuries with the colonial settlers, in addition to the millennia of years of meeting in this place by First Nations peoples.

I look around and there are bits of built environment for the campground here, and in the creek. There’s a toilet block behind us, there are pipes, a pumpstation, bits of concrete and a grate in the creek, but at the same time, it’s what’s here now, and it’s still kind of glorious!

Reflecting on that celebration of this place, and also the state of the world you’ve outlined, what does that open up for you?#

I think this is one of those paradoxical situations where you know that, whenever anything isn’t necessarily in its right state, when it’s kind of chaotic and we are buffeted by extreme events, that there will be a moment when things also come together, and where things will be right in place and in time. It makes me reflect on those ideas about celebrating and connecting—just being in the moment. Thinking back to a couple of years ago, it was nighttime, and I saw some people who had never necessarily been out of lockdown and out in Australia, since they had only recently arrived in the county. There were Ambassadors, kids from India, and a bunch of people who had likely never been camping before. To have all these groups out, with fires flickering in their firepits, pleasant, not aggressive, smoke spiralling into the sky, the laughter of children, and the bubbling of the creek, it was a time for celebration again.

The other thing I reflect on are the echoes and connections we make and bring to this place. Do you see this pink granite? It makes me think that our ancestors, including our familial ancestors, are always here with us. And I mean that in the broadest sense. Part of my family comes from Brittany on the “pink granite coast”, and to see that part of the family and their ancestors reflected and echoed in this place, along with the ancestors of people in Australia, the First Nations peoples, shows that we are connected intergenerationally and internationally. I know it’s now our responsibility to keep and care for this place for the next multiple generations. I think there is always something we can do, just to be able to come down, listen, take some time out to reconnect—it’s really special.

You mentioned a couple of the different modern and past human actors in the system. What are some of the other actors you observe, or feel are connected to this place?#

So I’m looking right now at a small stormwater outlet drain. And, just behind me as I mentioned, there’s an intake pipe that’s been catching bark debris as the water flows down the river.

There’s also a large cistern, and a block for camp sanitation with reticulated river water. The dispenser of fragrant pink soap I remember from my last visit has since vanished.

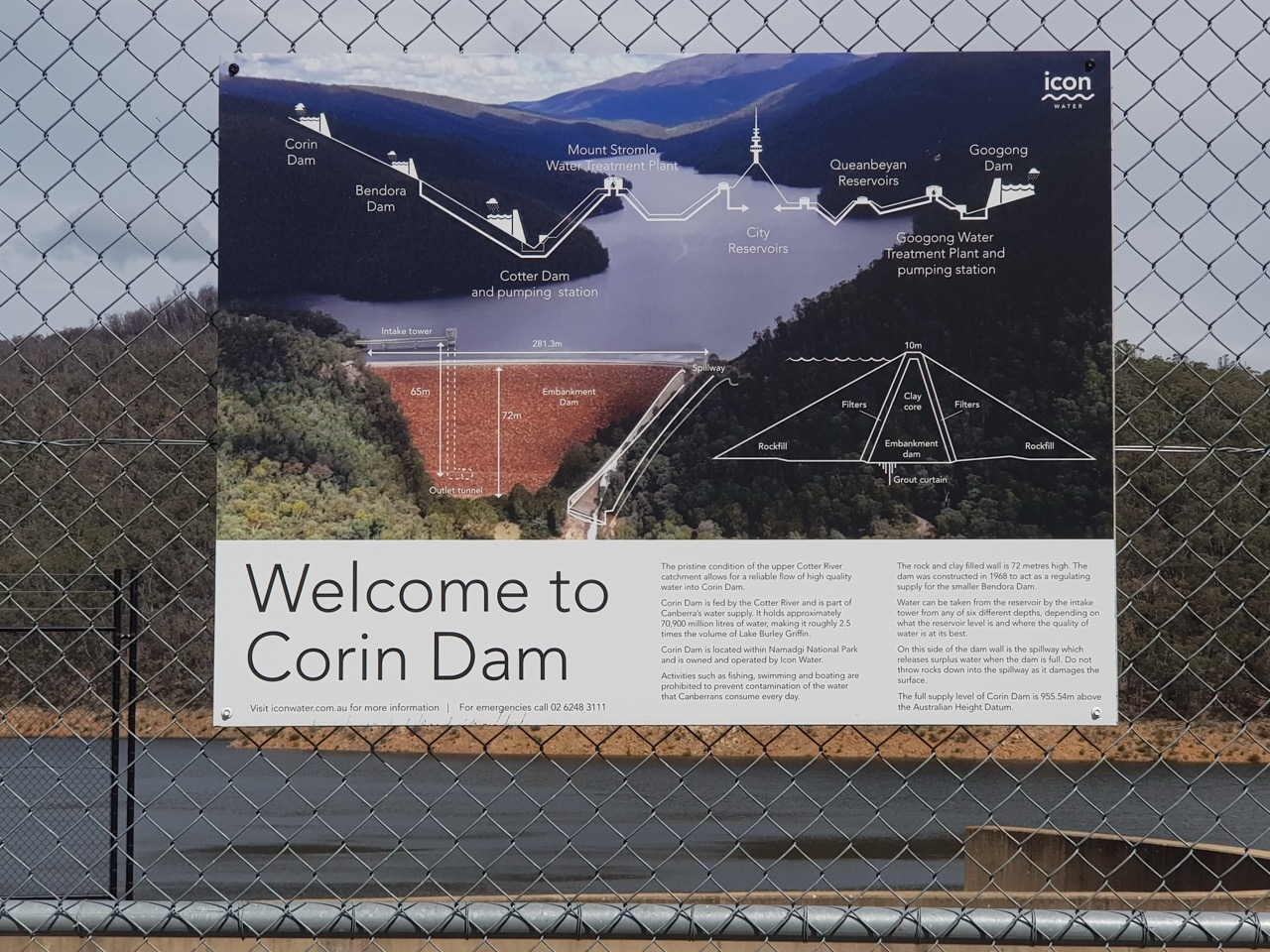

But then this place is also connected to all of the dams and weirs and other things upstream in the ACT, and indeed to the entire Murray-Darling Basin, which we’re a part of here.

So it makes me think that every piece of infrastructure, every actor in this place, is somehow connected to all kinds of other places and communities through our vast networks of relationships.

When I was just walking down this piece of stream a few minutes ago, I saw both some of the beautiful native plants of this region, but also invasive plants like blackberries and thistles. It’s interesting and hybrid; it’s a merging of a couple of worlds. You know we can eat the blackberries and might also be able to eat the yam daisies and other things that are here. Some people also come here to go fishing. But all of these things are connected. And when things get out of balance, like with the bushfires or the pandemic, all of that stops—those connections are disrupted. So it will be an interesting challenge for us—even just thinking from here outwards, about all of those other networks and their actions—to imagine how we might be able to organise them slightly more gracefully.

You’re talking a little bit about how it’s changed over time, and talking about sustaining some things over the coming years. Are there any changes to this place you think would be good, or good interventions that could be made?#

Every change has all sorts of ramifications, both positive and negative. Obviously, there are some really simple things here, like the invasive species, the blackberries. There’s obviously something to do there. Park rangers have tried to poison them for a long time and to rip them out, but they are particularly resistant to removal.

I think there is also the question of how this place is used. At the moment there are many people in the ACT who frequent it. There are many people who have lived here for generations or millennia, who come to this place to reconnect and to have a quiet moment. That’s made possible by the fact we’re in a place here that’s not typically connected digitally—there’s no telephone reception, there’s no easy internet access. As this level of connectivity changes, that is likely to change how it is experienced. And if this place ever becomes known more globally, that will obviously change how many people can come to enjoy it, but also changes relationships to others.

I’m quite aware of just how much activity is a reasonable and sustainable thing. I think we can probably think about that at the larger basin scales as well. Just how many of the different activities can be safely, responsibly, and sustainably supported? How much of the food growing? How much of the ability to create urban environments, and rural places where communities can live? How much access will be feasible for camping, recreation, spiritual needs, and places and spaces for all of those other actors: the animals, the river gums, and all the different species that depend on these kinds of water systems?

In terms of change, subtle change is probably a good thing, in order to ensure each little ripple has the desired effect. For this, slowly sculpting rather than completely upending things is likely to encourage more responsible custodianship, unless the systems are already dying and in need of rejuvenation. How we navigate change is complex, and part of what I see as responsible and reflective cybernetic practice. I’m sure when some of these bits of concrete and other technologies and environmental actors went into the creek, it completely changed what it was like—it changed its sound, it changed its feel, it changed how we could walk across it, bathe in it. And that’s the same thing at a larger scale with our Murray-Darling Basin. Just how fast we change things and how it occurs matters. So we need to support the ecosystems, and we humans as part of them, to thrive through continuous nurturing and purposeful custodianship.

One final prompt for you, I see there’s a bit of tension about sharing this place. For anyone reading this interview, what is one thing you want to tell them about Woods Reserve?#

I think this place, in some ways, is a laboratory for the future. This is where we experience the extreme ups and downs. This is a place of life, and unfortunately just upstream, also a place of death due to the treacherous and slippery rocky outcrops. And so thinking about what each place and connection means in the global system is a really important thing to do. Whether it’s extreme floods, extreme droughts and fires, or pandemics and invasion by actors not originally a part of those systems, these are things that will be experienced everywhere.

This place also allows us to reflect on extreme use, or lack of use: these are things everyone will have to think about, and everyone can learn from. This river, right near our home in the middle of our Murray-Darling Basin, like many other places around the world, provides glimpses into our futures, pasts, and presents—we just have to engage enough to notice.

Acknowledgements#

Interviewee:#

Prof Katherine Daniell

School of Cybernetics,

Fenner School of Environment and Society,

Institute for Water Futures,

The Australian National University

Interviewer:#

Dr Hannah Feldman

School of Cybernetics,

Institute for Water Futures,

The Australian National University

Production equipment:#

Thank you to D/Prof Genevieve Bell and Dr Paul Wrywoll for support and loans of audio-visual equipment used during the Riverwalk process.

Exhibiting in New York 2023:#

Thank you to Prof Carola Hein and Matteo D’Agostino from the UNESCO Chair Water, Ports and Historic Cities, TU Delft; the University of Leiden; and the Blue Crew.